Upside down and backwards

Reflections on printmaking, portraiture, and life in Brooke Stewart's "Bad Math" at the BCA's Mills Gallery

A print is a mirror. The inverted, negative impression of its woodcut. There’s a lot of calculation making one – you have to think backwards. But printmaking, like all art, is wrung from the heart and doesn’t always add up.

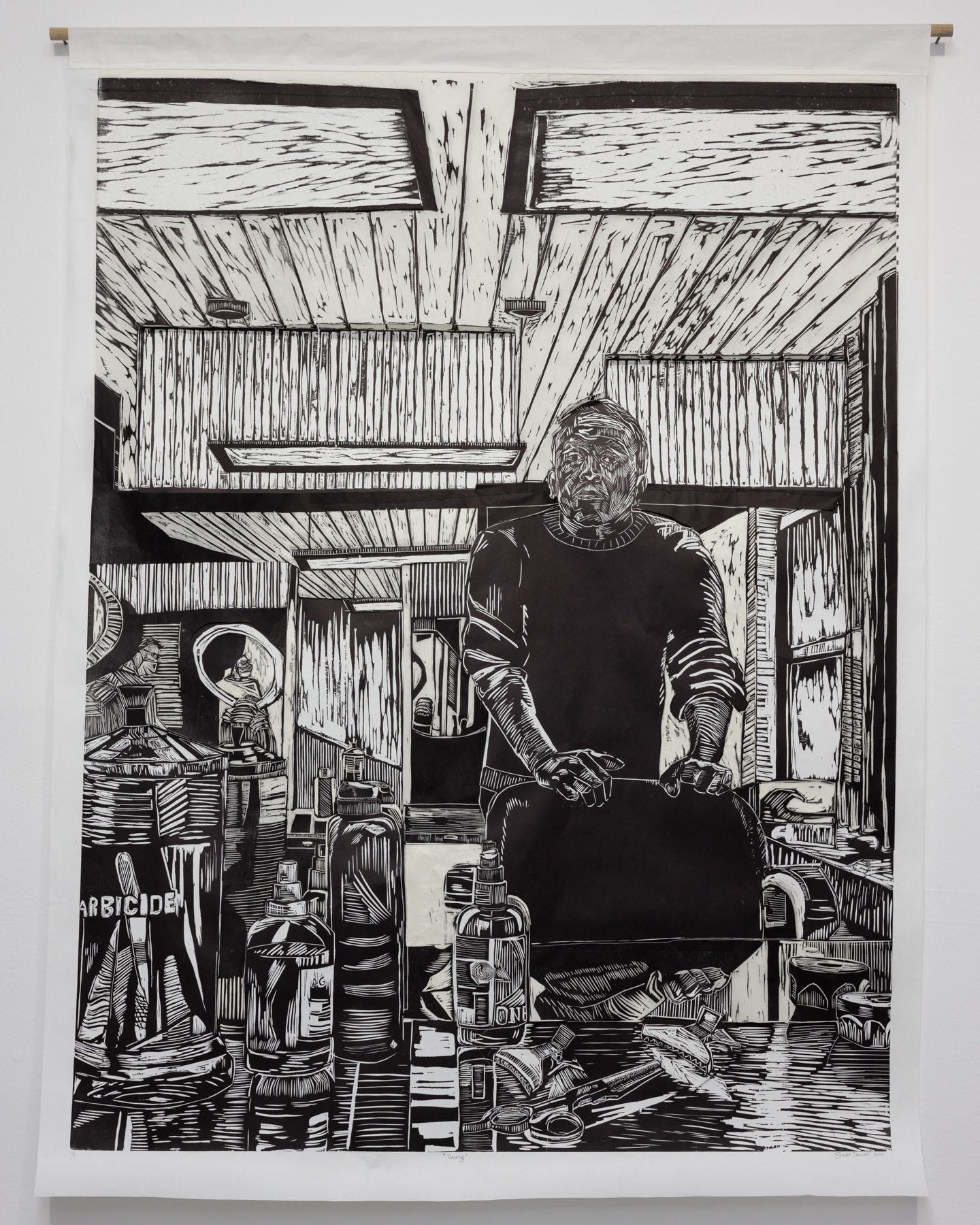

Brooke Stewart’s “Bad Math,” curated by Liz Morlock at the Boston Center for the Arts’s Mills Gallery through July 29, features large-scale portraits, and portraiture is a trek for any artist through the uncanny valley between self and other. Stewart depicts local artists, and she explains in labels how her subjects patch livings together, putting art and connection over first.

Woodcuts have their own stark aesthetic: splintery lines and often a black-and-white palette. In some ways, Stewart’s works echo those of great German Expressionist printers of the early 20th century such as the group Die Brücke, who shrugged off bourgeois values to emphasize humanism and emotional expression. Such groups – ateliers – tie printmakers together. Because they share presses, they often work side-by-side and collaboratively.

Stewart begins her portraits at their foundation: the paper. She crafts her own, adding to each pulpy slurry granular scraps from the life of her subject – cat hair, embroidery floss, garden clippings. It’s literally the stuff of their lives.

She prints her big woodcuts three times: Once on the handmade paper, again on cool-toned white paper, and also on warmer paper that’s closer to ivory. Then she sews fragments of these prints together with the tenderness of a quilter. The technique imbues another level of relief into what are, after all, relief prints – an almost sculptural interleaving that blows space into scenes that are otherwise easy to read as flat, graphic, and full of pattern.

In “George” (above), a portrait of artist and stylist George Amaral, tonics, gels, and a jar of combs and brushes in the foreground on white seem almost to jut beside an ivory passage. Architectural elements stand out in the same way – cool tone advancing, warm receding. George, in a black shirt, carries much of the ink, and the finger-print whorl of lines in his face becomes the nexus in a composition largely built on straight edges. In the distance, a client gets a haircut; we glimpse it in a mirror.

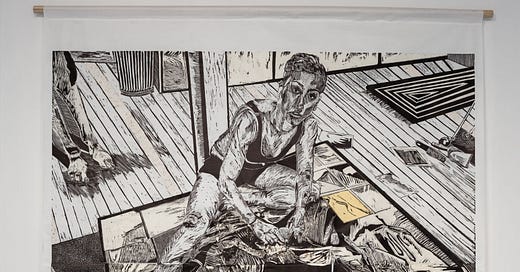

Stewart plays with dramatic foreshortening, telescoping images. In “Ria” (above), a portrait of artist Ria Brodell, the subject’s hand looms toward us holding a stylus. It’s as if we are a drawing being made by Brodell, who wears goggles outfitted with a loupe, the better to see us with.

The largest piece, at six feet square, is “Carving Out Self” (top). In it, the artist sits on a giant wood panel, at work on her self-portrait – self upon self. The print spirals, Escher-like, in an endless loop of the psyche. Much of the image, like its very making, is in some way inverted. It’s also upright and direct, with the artist smaller but more fleshed out on cool white, popping off the surface to meet our gaze.

That looping and mirroring is what makes a print. It also makes a portrait: the Mobius strip between an artist and a subject. And while we’re at it, the mirror is there, too, between a viewer and a work of art. There’s always an alchemical unknown between the two. There’s always a relationship.

In these exacting, laborious prints, Stewart offers a picture of the mirror itself: The out-of-control moment an impression is made.

(Photographs: Melissa Blackall, courtesy Boston Center for the Arts)

Correction: George Amaral was initially incorrectly identified as a Black man. He is not.

I love the rhythm and the sound effects of this sentence: "Print making, like all art, is wrung from the heart and doesn't always add up." The assonance in "all-art-always-add-up" and the rhyming of heart and art are a reflection in sound of the woodcut process. This is good tight writing. I also love the phrase "uncanny valley between self and other". "uncanny" and "valley" near rhymes showcase the connection and difference between "self" and "other". The consonance among "portraiture" "trek" "artist" and "through" mirror the trek through the valley. You probably do this stuff instinctively and unconsciously. It shows a great command of language.