The substance of wisps

Vaughn Sills's photographs at Kingston Gallery and Charles Suggs's smoke paintings at Bentley's RSM Gallery

Leo Tolstoy packs dynamite into throwaway descriptions In quick succession in “Anna Karenina” – he describes each of two characters with a pair of adjectives: “naïve and dreadful,” and “sickly and ecstatic.” Brief, tense, evocative.

Tensions like that set boundaries around an unknown. A feverish energy vibrates between “sickly” and “ecstatic.” There’s a bigger gulf between “naïve and dreadful” into which I project willful ignorance.

Joy and sorrow span a much smaller space. They’re energetic kin, each close to the heart. They intermingle rather than pull against each other; together, they become bittersweet.

Each photograph in “Joy and Sorrow Intertwined,” photographer Vaughn Sills’s show at Kingston Gallery, sets a still life – a plant in a vase; a remnant of a tree, all gathered from Arnold Arboretum – before a skyscape from Prince Edward Island, her homeland. Roses in full blush glow against a sky heavy with clouds in the title work. But golden sunlight sneaks out and underlines the blossoms, a glimmer that rhymes the still life with the skyscape, the transient moment with the eternal.

That particular tension, in which our sense of time dissolves, is the definition of creative flow, of enlightenment. But it, too, is bittersweet. Something is bound to come along and upend it. In “A Secret About a Secret,” Vaughn portrays an unraveling wasp’s nest, papery, gray, no longer inhabited. It broadcasts danger and fragility.

Diane Arbus said, “A picture is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you, the less you know.” This photo is, like Tolstoy’s descriptions, packed with information and unknowns. There’s a handwritten note tucked beneath the wasp’s nest. Crepuscular light peaks out, but the sky here is ominous. Light fades. What is in that note? Will it sting?

The artist titles many photographs with literary lines. “A breath of breeze carries a half-remembered dream” is from Lowry Pei’s poem, “The New Thing.” (The writer is Vaughn’s husband). In the photograph, a milkweed plant explodes in silken puffs from desiccated pods – each a wisp shedding the skin of yesterday, flying off on today’s breeze to drop its seeds and vanish tomorrow.

I thought of Vaughn’s milkweed when I saw Charles Suggs’s smoke paintings at Bentley University’s RSM Gallery. Painting with a candle flame seems chancy – the medium has its own agenda. Charles learned the technique on a visit to Cape Town, South Africa in 2018. During the pandemic, it became a medium of choice.

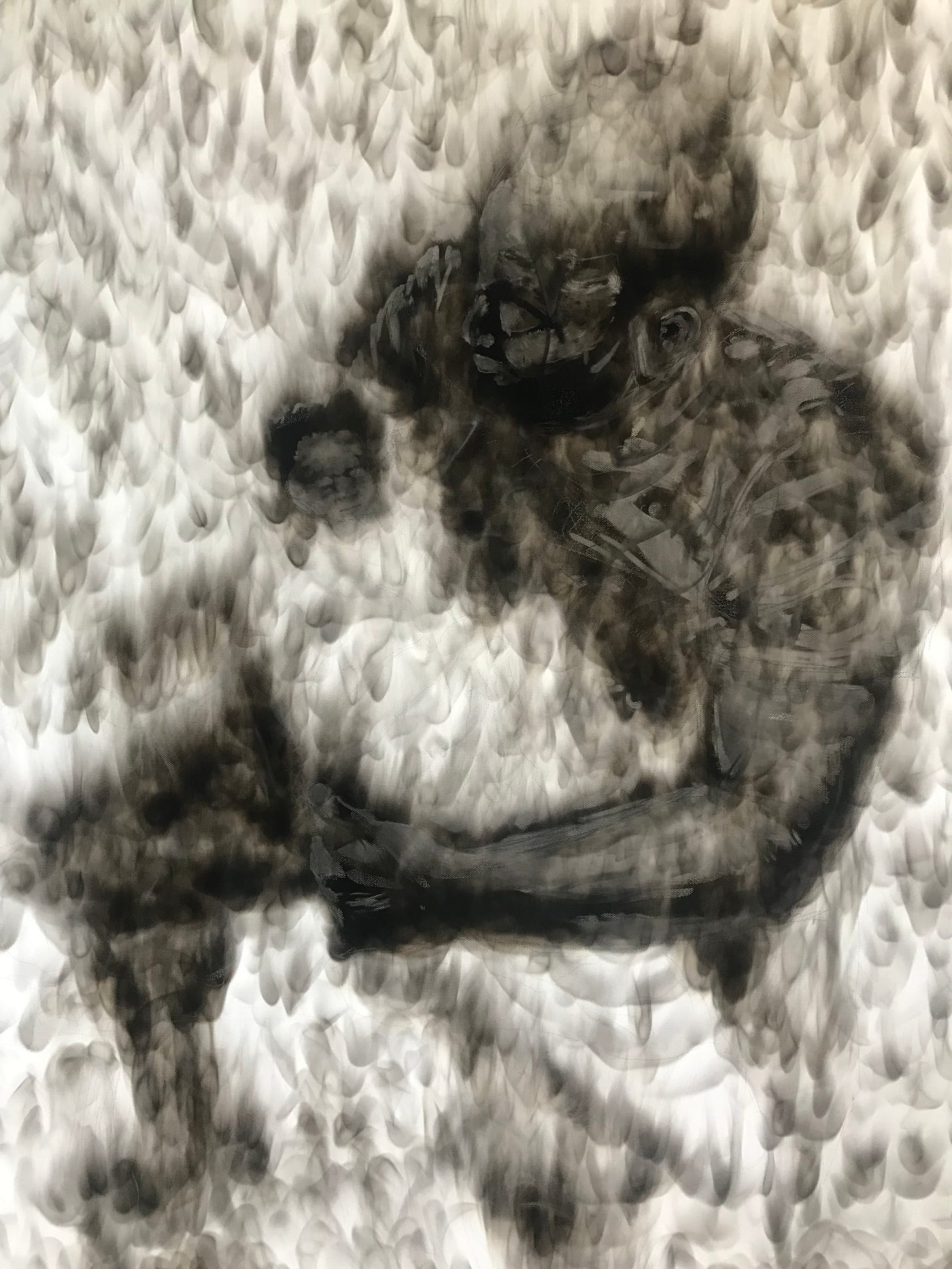

Fire is elemental– there’s something almost shamanistic about using it, and this exhibition is aptly titled “Conjuring.” Charles paints smoke portraits of friends and family. He works from memory and from photographs, so already he’s a step away from the person in the flesh, leaning instead into his felt sense of his subject.

It’s possible for an artist to be somewhat exacting with smoke; look at smoke paintings by Sheila Gallagher and Rob Tarbell. Charles makes more expressionistic portraits, starting with a precise underdrawing in paint. Then he hangs the panel overhead and takes a candle to it.

From a distance, figures appear ethereal. Get closer, and elements of the underdrawing suddenly add contour and substance – lips, eyes, nose. It’s a startling effect. Like that eternal moment in some of Vaughn’s photos, it collapses parallel experiences, but instead of time, here we have relationship: a felt sense of someone, and the visual fact of him.

Charles, a Black artist, has made works that bring up issues of history, racism, and invisibility. What hasn’t been spoken. Secrets about secrets. Here, licks of soot soften and obscure his subjects, creating, like Vaughn’s milkweeds, a suggestion of transience. In portraits, they inevitably suggest a veil.

What is that veil? It could memory – the smoke of emotion, connection, and personal history that can’t be touched but is the substance of relationships. In “Memory,” a man holds an infant. Painterly gestures vibrate around the pair; they seem to kindle into being from that sooty hum. The tender scene feels spun from sense memory: I felt the weight of a baby, the warmth, the smell, the gentle smacking of lips during sleep.

.In each of these paintings, the veil lifts, and we read the contours. Visibility snaps in, and is as quickly lost. In “Specters,” three men seem to form out of wisps and clots of smoke. Their edges dissolve in sooty tendrils; their bodies flicker. They appear insubstantial, yet they are riveting.

That toggling between seen and unseen awakens in me the same alertness that Tolstoy’s descriptions do – who are these men? What do I know about them, and what don’t I know? It’s not an intellectual process. Rather, I feel my way forward, making meaning informed by my own history and by what the artist has given me: Smoke and gestures. A still life and a skyscape. They open our imaginations up, and we jump in.

Images, from top: Vaughn Sills, “A breath of breeze carries a half-remembered dream,” dye sub aluminum, 24x36, 2021 and “A Secret about a Secret,” dye sub aluminum, 24x36, 2023. Charles Suggs, “Specters,” smoke on Rives BFK paper, 2023 and “Memory,” smoke on canvas 2021. Photos courtesy of the artists.

Your description of smoke paintings is fascinating. And I loved the way you wove Tolstoy's imagery into this appreciation. Very artfully done. I can't think of the name for the device using apparent contradictions as in substance-wisps, but I loved the way you held the piece together by the use of it.

I've never seen smoke paintings before. They're intriguing.