Artist Deb Todd Wheeler has been in the woods since September 11, 2017, when her son Lucas died suddenly at 18 of an undiagnosed heart issue. Later that week, Deb and her husband Andrew and Lucas’s younger brother, Eli, sought a scrap of solace in the woods at Skyline Park in Chestnut Hill.

The family was assaulted by the racket of chainsaws clearing the earth of trees. The area, a former landfill, was being remediated. Since then, there have been new assaults: Deb’s brother and collaborator, filmmaker Rob Todd, took his own life in 2018. That same day, Andrew received a cancer diagnosis. He survived and is well.

Deb has been tracing the path of her grief through this same forest to Lost Pond. In the woods, with many helpers, she created a shrine for Lucas, and then “RADIO SILENCE,” a short hike (but not always an easy walk) with guided, geo-located audio to and from the shrine. She takes people on this path with Puck, the rescue dog she got after Lucas died – a big, shaggy, comforting presence. By now, she has walked it with hundreds of companions. I joined her in late June.

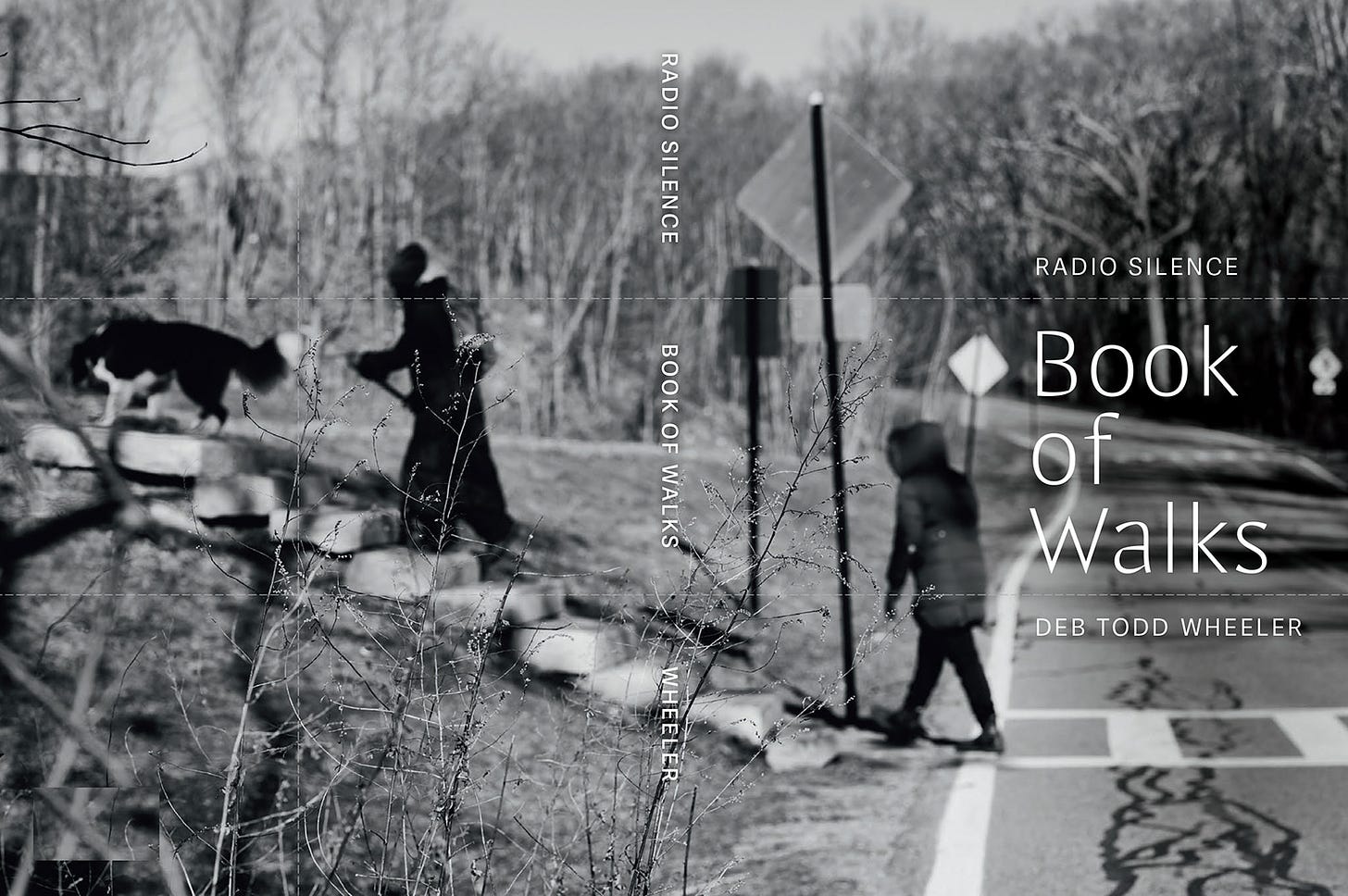

This September, Deb will publish “RADIO SILENCE Book of Walks.” Proceeds from sales are going to The Children’s Room in Arlington, which provides grief support to children, teens, and families. It’s a gorgeous book with photographs by Deb, Kelly Davidson and Elijah Mickelson, and lyrics from Deb’s songs, which play during the sound walk. The walk, the book, and the soundtrack map experiences of grief. The book features conversations she’s had along the trail.

“RADIO SILENCE Book of Walks” has a stillness to it. It’s like a capacious stopping point, a place where it’s safe to feel your way into the crannies of loss and love.

Loss does not, at first, feel roomy. How do you go on? How, even, do you breathe and eat and talk to others? In time, you start to excavate, like the landscapers at Skyline Park. You begin to find a path in the airless dark, discover markers. In time, there are places to put some of that pain and for new growth to emerge.

Years ago, I hiked in the Blue Hills every week with my friend Jim Moran. He was a Buddhist, a writer, an actor, an Air Force vet, and a salesman who sold chemicals and solvents to autobody shops. He was a good man who struggled and learned and tenderized as he grew. Every evening, in the days before Twitter, Jim wrote an email to a select group of friends, “Notes from the Quarry Bud-duh,” distilling his day into a koan reflecting on the pain, joy, and ridiculousness of life.

In 2004 Jim was diagnosed with lung cancer. He died two years later. Each week during his last few months, I’d stop by the home he shared with his wife in Belmont. “Sister Cate!” he’d call out when I came in the door. At first, we walked together through Highland Meadow Cemetery. In time, he couldn’t leave the house. He entered home hospice care, rail thin, frail, furious. It scared me to see him so wracked, so condensed. Two weeks before he died, he dictated to me his last Bud-duh note, signing off. “I hope I have been of some service to you all,” he wrote.

Showing up for the dying is precious and it wrecks you. Anticipatory grief, like the grief that follows a loss, suffocates. Time stops.

I’m in a different season now, as Deb and I set out on our hike, one that feels more like spring. I turn on my voice recorder. I’m here to report and write Deb’s story. As we walk, we talk about Lucas and Rob. We talk about grief. Deb’s words are wise, questioning, open.

“Radio Silence” is like a labyrinth: An internal walk as well as an external one. We make our way, silent and single file, through the sound pools. Consecrated places along the path.

“For crying out loud,” Deb’s voice sings in my earbuds. The song is called “Plea.” “Would anyone notice if he’d up and gone?”

She wrote the song before Lucas and Rob died. The second lyric seems to point to Rob’s pain. But it’s the first that hits me. I say that a lot: “For crying out loud!”

The older I get, the more easily I cry. As a child, I wasn’t given the tools or space to talk about my grief after my parents separated. I was stopped up, my feelings corked. Now tears flow more easily.

We arrive at Lucas’s shrine: branches propped against each other like a shelter, like a bonfire. At the front, his photograph: A handsome, vital, young man with a puckish grin. “THE BOY WHO LIVED, LOVED, LOVES” is engraved in a bare branch. The shrine evolves as people leave offerings: stones, jewelry. Today, Deb brings hydrangeas, and we put their stems in the soil. This is a place for Lucas and also for anyone to stop and tend what ache needs tending.

I look at my voice recorder. It’s off. It cut out as soon as we stepped into the first sound pool. Oy! And the interview has been such a garden of good quotes!

But maybe this hike is not intended to be recorded. Interviewing can be a shield. I don’t turn the recorder back on. Instead, I tell Deb about my Substack. How I want it to be less about reporting, more about creating. More personal.

Well. Here we are.

We continue along the path, down and across a new boardwalk. It makes the walk easy over a mucky bog. For quite a while, Deb had to navigate the bog stepping from one tangled root to another, fearful of slipping in. We’re silent as the song “Surge” plays in our earbuds.

“You step into the water ’til it covers your hair,” she sings.

Maybe the hardest part of grief is surrender. We stiffen, we resist. Then we step – or just as often, slip and fall – into the water.

The sun glints off Lost Pond. The walls of the transfer station stand on a distant ridge. Someone has etched illegible glyphs into the wood of the dock. We lie down on benches and listen to a bullfrog croak.

“When I first came here,” Deb says, “there was a chorus of bullfrogs.”

She writes in “Book of Walks: “Conditions must be right here for life to happen, to go on. I don’t know if toxic residue can ever be fully purged.”

She sees Lost Pond as a nonhuman collaborator, she says, and this brings up another grief: We live each day with the horror of what’s happening to this beautiful earth. We struggle with what we have done wrong; how strong we thought we were; how terribly weak and faulty we turn out to be. We have a lot to grieve, and we don’t have a society that really makes space for it. Art does.

A loud splash, and we sit up. Puck has jumped into the water up to his head. Deb pulls the big, soaking pup from the mud, and he gives a good shake. We start off again, moving toward the end.

Up to now, Deb’s songs have been mostly acoustic, threaded with other sounds – Lucas’s laughter, birdsong. They create a time helix that miraculously syncs past with present. This song for which RADIO SILENCE is named is harsher, full of guitar shreds and static and electronic Emergency Broadcast System blares. I wince. My body tenses. I don’t want to be here with this.

Blaring silence is such a vast and sucky part of grieving. All we can do is take another step. But this is part of a helix, too, the one that courses between denial and acceptance, clinging and letting go. Maybe, in time, these binaries are integrated. Loss and love become one.

In the last week of Jim Moran’s life, unable to find words or hope, I went into the movement studio and hunched into my resistance. I felt I was carrying a black ball of death on my back. I stooped and plodded. God, it was heavy, and I just kept walking, exhausted, numb, resentful. Then I pulled it off my back and held it in front of me.

In a flash, it seeped into me. It wasn’t a rock – it was electric! Was this a ball of death, or the edge of transformation? I felt my own aliveness. I felt my love for Jim, a thread of light I knew would never break. I ran around the studio. I danced. I cried. All that was different, really, was that the fear was gone.

Then Jim died, and I had another boulder to carry. But years later, love and loss have integrated. I can still hear Jim calling out, “Sister Cate!” Gratitude wells up. Tears come.

“RADIO SILENCE” is Deb Todd Wheeler’s black ball of death. As the landscapers shaped this landfill into a park, Deb carved a way of sorrows through a bleak wood, planting seeds, casting out lifelines. As we near our cars, she tells me she’s not interested in art for art’s sake anymore. She wants to be of service.

We walk on.

Photo credits, from top: Kelly Davidson, Kelly Davidson, Deb Todd Wheeler, Deb Todd Wheeler, Deb Todd Wheeler, Elijah Mickelson, Deb Todd Wheeler

Breathtaking. Shattering. This side-by-side journey of loss, grief, and love has me in grateful tears.

Beautiful gift of talent & wisdom ✨ many thanks for this version of capture 🙏 the important work