Figures and the art of composting

Sally B. Moore and C.A. Stigliano in "Figuring Our World" at Brickbottom.

Hello readers! Today is my birthday. To celebrate, this post is free. Thank you for following Ocean in a Drop! Please share it around, and if you haven’t already, consider a paid subscription. It helps keep the lights on. Also, today is National Punctuation Day! Please celebrate wisely.

Artists have a long history of playing witness to horror. Goya’s “Disasters of War” etchings documented the Peninsular War between Spain and France from 1808 to 1814. Picasso painted “Guernica” after Nazi Germany bombed the Basque town in 1937. Artists make such works out of sympathy and outrage, but there’s a third motivation. Chaos and violence have a viral quality; they infect us with fear, dismay, anger, and resistance. Throats tighten. Backs stiffen. Making art about the evils of society is one way to expunge those ghosts, however briefly, from our systems. Give something form in the outside world, and the burden inside is not quite as heavy.

“Figuring Our World” at Brickbottom Gallery brings together sculptors Sally B. Moore and C.A. Stigliano. They’ve known each other for years, but they’ve never shown together before. Chuck is a wood carver. Sally uses a variety of mediums – paper clay, wire, plastic, paper. Their figures embody the ghosts and monsters of the world, the dark energies that inevitably come to inhabit and shape us – and it sure seems like there have been a lot of them lately. We must contend with them, or we will succumb.

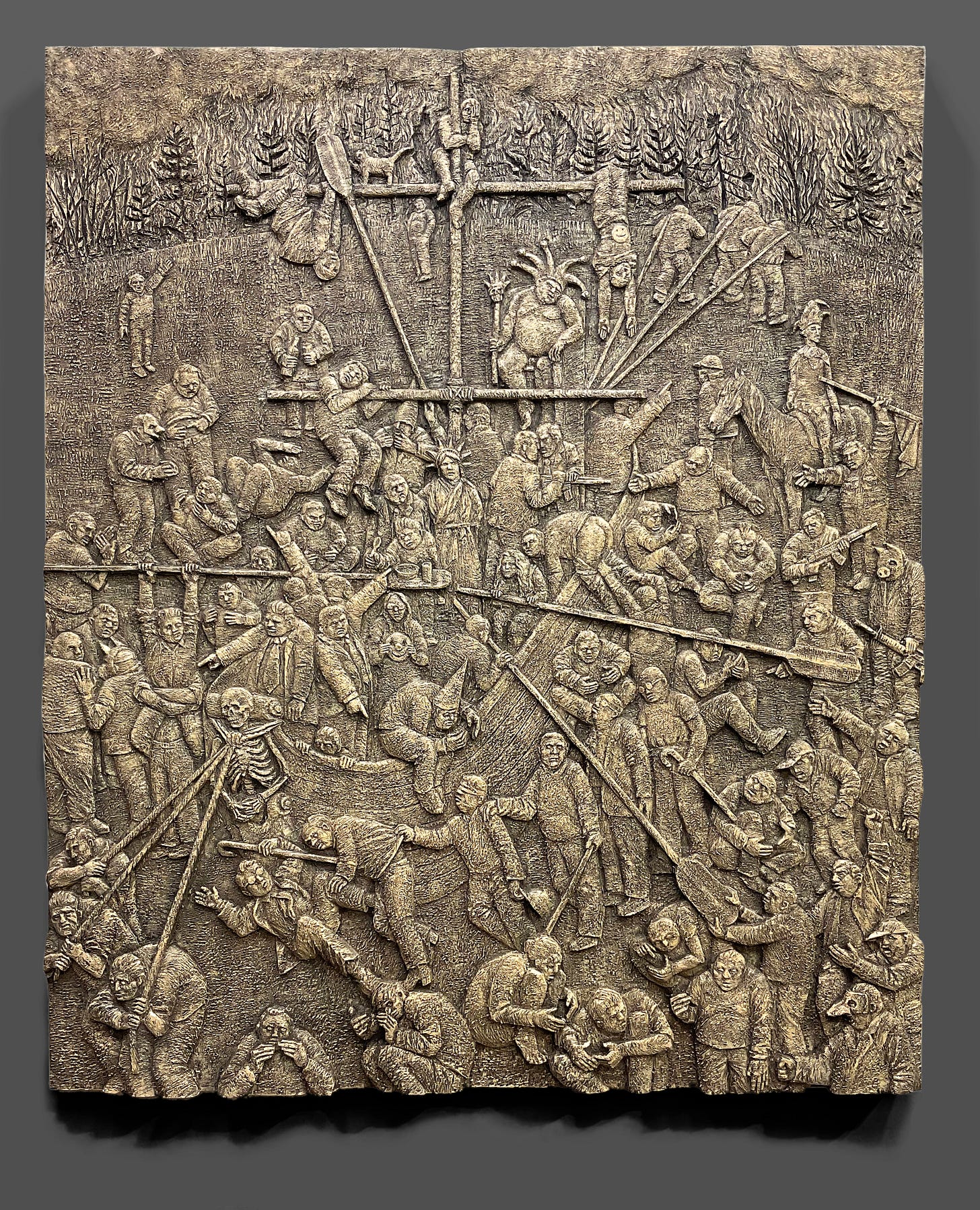

These two artists have had parallel careers over three decades, and they come at societal evils from different perspectives. Chuck’s sculptures, especially his bustling, Boschian relief works, comment on the lunacy and threat on parade before us. Sally’s lone figures recall Alberto Giacometti’s: harrowed, wind-whipped and gaunt, they represent what it’s like for a person to live in the direct line of the dragon’s breath of dysfunction. They head frantically in the wrong direction, or they light the very matches that will destroy them.

They all take form as living nightmares,

The aggressors in Chuck’s work may be powerful, but they’re puppets and fools. There’s an emptiness to even the most solid of them. Look at the teeming clown car in his “Ship of Fools/Sea of Fools” relief – a depiction of the U.S. Congress. The characters wear dunce caps and blindfolds; they point fingers; they stare at cupped hands where cell phones might be. This modern-day take on Hieronymous Bosch suggests that humanity has not evolved much in the last 500 years.

Chuck’s brilliant, ferocious “Warthog God” (top) bedecked with pink flowers and cuffs on its horns, has an echo in Sally’s rough-hewn “The Last Rhinoceros.” Black rhinos are one of the world’s most endangered species; this one appears weighed down by a human on its back. Chuck’s represents a greedy God; Sally’s, a beleaguered beast on the cusp of disappearing. Seeing them so near each other suggests the two are somehow one. The warthog lights the match that consumes the rhino.

In several graceful confluences, one artist moves right into the other’s territory. Sally’s “Swamp King,” a crocodile in a suit with a red tie with the American flag crumpled at his feet, is every bit as monstrous as the skeleton astride a horse in Chuck’s “Triumph of Death,” a callback to Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s 1652-3 painting of the same name, in which an army of skeletons ravages a town.

And pity Chuck’s “Marlboro Man.” Marlboro Cigarettes’ epitome of American masculinity and rough-hewn individualism – the lone cowboy, maker of his own rules – sits on a cornered, frightened mount, burying his face in his hands. He’s not all that different from Sally’s “The Human Race” (above), a blindfolded wire figure sitting backwards astride a fleeing horse. The prickly wire, the bits of fabric flying in their wake, make the rider look tense to the point of brittleness, stuck on a fluid, graceful beast.

So what are we to do? We all have to compost the stinking refuse that comes our way. Sally and Chuck do it by shaping it and putting it back out in the world – like the flowers and cacti that can grow from the mulch – to show us who we are. That helps. Because these sculptures call and echo, the triumph of “Figuring the World” is that while it laments and makes fun, it doesn’t let any us off the hook. We are all fools, we are all Swamp Kings, we are all endangered, we are all Marlboro Men. And as long as we can recognize our own humanity maybe we can see it in others and find compassion.

Finding compassion is so important

Densely moving and scary.