Feeling "STUFFED"

At BU Art Galleries, everything is filling

Friends, do you ever feel lumpy? Crepe-y? Pimply? Dimply?

Do you ever feel… not so fresh?

I’m pear-shaped. That sounds like an objective description, but for me it’s tinged with shame. When I was in college in the 1980s, I thought I had a weight problem. After I poured over “Fat is a Feminist Issue,” I blamed my father for it.

I did not have a weight problem. My dad was a good man who did not deserve my ire. But jeez, the way growing up in a patriarchal, capitalist society can play with a girl’s self-worth! God forbid a femme person should feel… well, not so fresh. Masculine types, that’s another matter. They should feel free to stink to high heaven.

“STUFFED,” a terrific exhibition curated by Mallory A. Ruymann and Leah Triplett Harrington at Boston University Art Galleries’ Stone Gallery is lumpy, dimply, bulbous, and droopy. It ties together painting, soft sculpture, and textile art with materials such as batting, upholstering, and filling.

Inevitably, it rings with references to the body, especially bodies that have been objectified and critiqued, bodies that have been targets of loathing. Women’s bodies. Queer bodies. Black bodies. Short bodies. Disabled bodies. Any body but a Barbie body (or a Ken).

Our poor bodies. How exquisite they are, what sources of pleasure, solace, self-knowledge, and knowledge of the world! What have we done, to question their freshness, their worth, their wisdom?

Many artists in “STUFFED” weave textiles with painting, making a direct link between a medium long associated with the traditionally feminine domestic arts and the largely masculine Modernist approach to abstraction.

It begins brilliantly with an Elizabeth Murray painting from 1964. You’ve heard of Lucio Fontana, who slashed and punctured his paintings, violating the sacroscanct picture plane, starting in 1948. In the 1960s, Murray stuffed paintings. “N.H. Lockwood,” on view here, is a lulu. A woman’s nose bulges off the surface of a portrait within the painting. A hand enters from outside the portrait to apply lipstick to the woman’s mouth.

Murray’s painting asks: Who is real and who is painted? What does “painting” mean if we’re talking about a painted lady?

Another stuffed painting hangs catty-corner across from “N.H. Lockwood”: Meg Lipke’s “Big Pink,” a nine-foot-tall canvas in the shape of a painting stretcher, ballooning with polyester fill. It’s 11-plus feet across, pink, and adorned with expressionistic gestures in orange and yellow. But it’s not rigid like a stretcher; it sags as if it might collapse and hold you in its embrace. Nearby, the soft, tubular filled frame of Jai Hart’s “Hopscotch” spills off the wall, inviting viewers to come play on the patterned painting it contains.

In Modernism, the mechanics that realism had hidden came to the fore – flatness, support, pigment, brushwork – to call attention to Painting itself. Championing Abstract Expressionism and Color Field painting, Clement Greenberg made a case for purity. But such ideas had an intellectual ascetism separated from the body. It was partly the times, as “Designing Motherhood” spelled out so starkly last year at the MassArt Art Museum; Modernism developed alongside a societal distaste for the unpredictability of the body — particularly ones with uteruses — which can be so irrational, so eruptive, and so fluid.

These days, the notion of purity has an unsavory whiff of whiteness, patriarchy, and totalitarianism.

By the end of the 20th century, content was surging back into art, countering all that form (it had always been there, just subverted). Personal stories. Identity art. In the 21st century, femme artists have explicitly taken the ground Greenberg staked. “Simpatico,” a terrific 2012 show at the BU Art Galleries curated by Kate McNamara, featured women abstract artists who delighted in the goopy physicality of their materials. Their work was about play, not the torment or sturm und drang of their Abstract Expressionist forefathers. Sheer joy in the mess.

“STUFFED” is a mighty sequel. This time around, the works are just as fun, but messy in a different way: They’re fleshy.

Amelia Briggs’ fiber-stuffed paintings resemble abstract cartoons, wormy and bright and ruffly. Anne Libby’s quilts speak right to art history’s masculine/feminine divide, turning photos of modernist architecture into quilts, pixelating and melting all the hard edges with satin and batting. Nastassja E. Swift’s “we have to fight, although we have to cry” sags on the wall, with little felted wool heads sprouting out like seeds on a pomegranate.

Some artists jump entirely off the wall into sculpture. Rose Nestler’s “Ballet Bag” suspends an ample pink duffle on a barre, with two muscled pink legs extending up from it in a spread eagle. The purity of ballet foiled by baggage. Dang. Baggage always shows up, doesn’t it?

Pure formalism can have mystical qualities, like that of Hilma af Klint, and we humans need that. But what’s great about “STUFFED” is its not-so- fresh hedonism, its grappling with shame as well as sensuality.

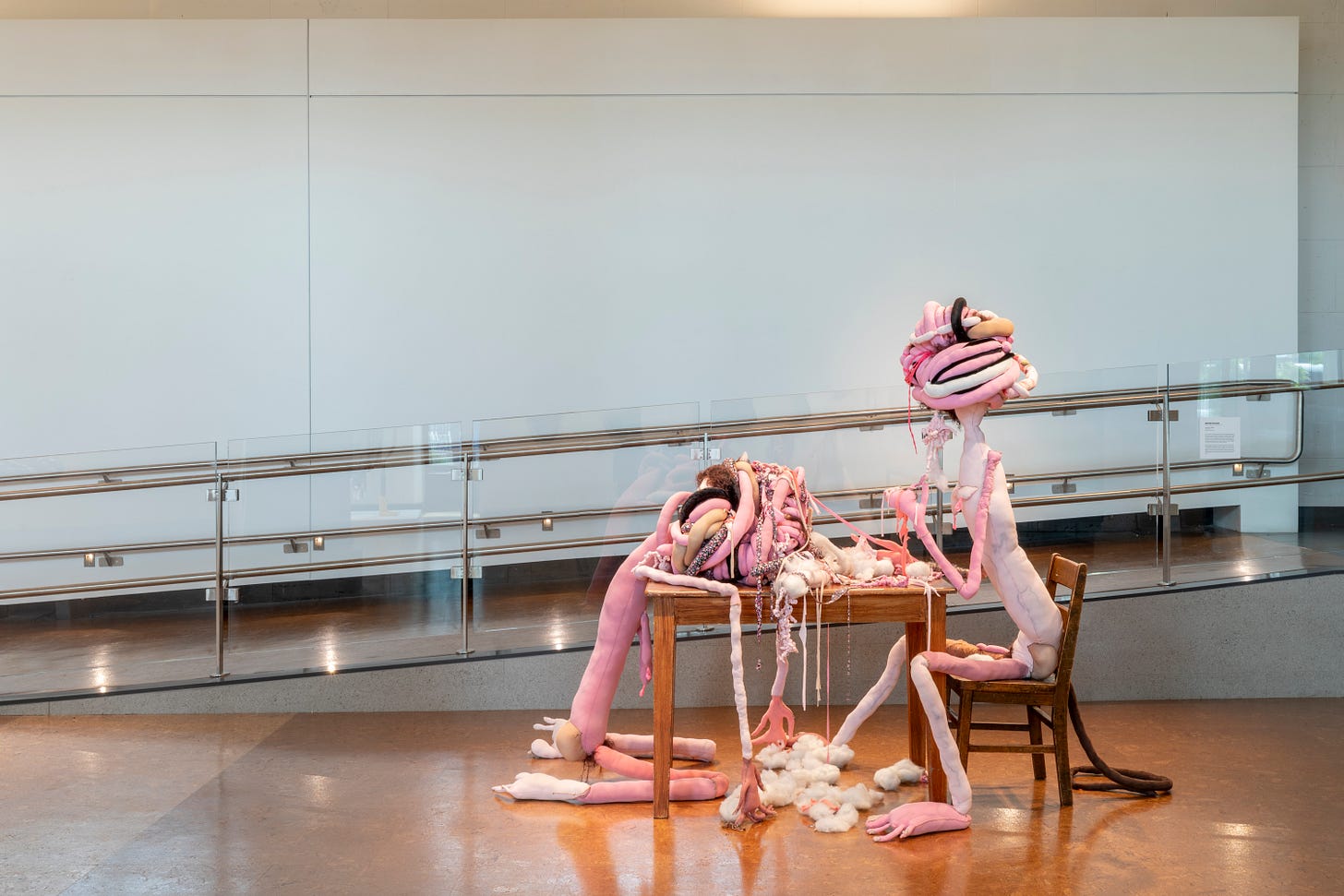

“Lunch,” BSisters Khaleghi’s human-scaled sculpture of a Pink Panther-like beast with a head as loopy as intestines sits at a table and feasts on the entrails of another critter.

The purity thing is a sham. Everybody bleeds, sweats, and poops. What’s inside is outside; what goes in comes back out, and we’re all, in some ways, cannibalistic. Art is, too. A central tenet of Modernism was self-critique, and artists have been queering binaries for ages. Limits will always be tested, so paintings will swell; stretchers will droop and soften – until they don’t.

We’ll see what comes next. Surely, it will be fresh. And maybe stinky, too. Or …not so stinky?

Images, from top: “Lunch,” BSisters Kaleghi; “N.H. Lockwood,” Elizabeth Murray: “Big Pink,” Meg Lipke; two works by Anne Libby; Rose Nestler, “Ballet Bag.” Photo credit: Mel Taing