I’ve never been much for New Year’s resolutions – the annual tradition feels too formal to me. I’m not always ready, on any given January 1, to start fresh. Blanks slates come when they come. But I do remember one resolution quite clearly. Many years ago, I was visiting friends near Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts, for the holiday. On New Year’s Eve, we went out for dinner at a candlelit little bistro overlooking the water. Somehow, in this intimate setting, the idea of a resolution felt suddenly less like an edict of personal improvement, or a goal to relentlessly aim for. Instead, it felt like a promise to a part of myself I’d long ignored.

“This year,” I said, “I want to follow my heart.”

My heart had been largely hidden for much of my youth and had only recently made itself evident to me as a possible north star. I’d previously navigated life doing what was expected of me, or what I guessed was right. Following my heart seemed, in the moment, wildly risky – there was nothing to strategize, no way to plot a path! – but I knew it was the only way to go.

I had a stellar year. This year, I pray to open, drop in, and listen.

I believe that making art mirrors life. Don’t force it. Get your ego out of the way. Pay attention, follow intuition, and see what arises.

How do you begin anew? I asked several artists how they start a work of art. Everyone roots into what moves them. It might be materials, process, place, building on past work, or structure. Whatever it is, it opens the field of play. Artists get quiet, drop in, and let themselves be guided by intuition, the work itself, or whatever the hand does next. For 2023 ICA Foster Prize winner Yu-Wen Wu, “How I begin a work of art depends on the piece and the medium. There is a period of contemplation (sometimes minutes, sometimes months) before I understand how ideas develop. When I feel ready to begin, I take a few moments of focused deep breathing, find an internal quiet place then dive into an intuitive and meditative space of making.”

Here’s what others said.

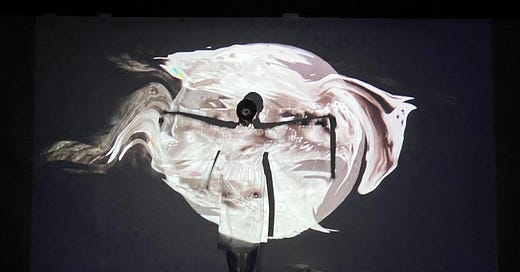

Soyoung L. Kim: Often, my works grow out of projects I had been working on, usually because I find there is an aspect to the work I didn’t have the space to address or I need to dig deeper into something I uncovered while making a previous piece. I believe in creating worlds and so with each work I make, what keeps me going is the question, does this transport a person to my world? Soyoung’s “Confessions of a SunYeo: For Umma,” pictured at the top, will be featured in “Painting&,” opening Jan. 18 at Boston University Stone Gallery.

Gerry Bergstein: My main method of starting a work is by painting the canvas black. When that dries, I go over the whole thing with a very slow drying white. Then I scrape into the wet white paint with various tools in order to get a baseline structure. This process is almost like etching. Slowly over a period of weeks spaces and images magically appear to me. This involves leaving the painting for a day then coming back to it and surprising myself with what I see the next day. I am basically doing long-term rorschaching . I find the process magical.

Elaine Spatz Rabinowitz: It’s always the last work that gets me started on the next. Because the last work is never all that it could be. By its very Insufficiency it drives me to try again, to push something further, often in the casting process.

I’ve been thinking lately about another related matter: the unspoken grief and mourning that’s part of any “process” painting; insofar as one has to work over and on top of old areas in order to lay in the new ones. I think it was in the making of this painting that I realized how much I was grieving parts that had been vanquished. I tell my students what Picasso said: “if there’s a part in your painting you really like, take it out.” Was it really Picasso? In any case it’s good to dissect what that means with the students. One has to learn to discard, in art and in life! Elaine’s new show “Sublime Vestiges” is at Anderson-Yezerski Gallery Jan. 5-Feb. 10.

Dell Marie Hamilton: How do I start a work of art? That is a great question, and it varies because I work in a variety of mediums. If it's a performance artwork, the first thing I do is a site visit. I'm really sensitive to space so the location, its sightlines and architecture will give me ideas about what I want to do. After visiting a site, I usually conduct historical research to gain a better understanding of the context. That said, in most cases, the materials themselves will guide me. For the piece I made for the Deeply Rooted: Faith in Reproductive Justice show currently at Brandeis, I'd been experimenting with synthetic hair, tulle and finger cots for some time. By allowing my hands to lead me, I've learned to trust that my process will rise to the occasion. “Deeply Rooted” is at Kniznick Gallery at Brandeis University’s Women’s Studies Research Center through Feb. 1.

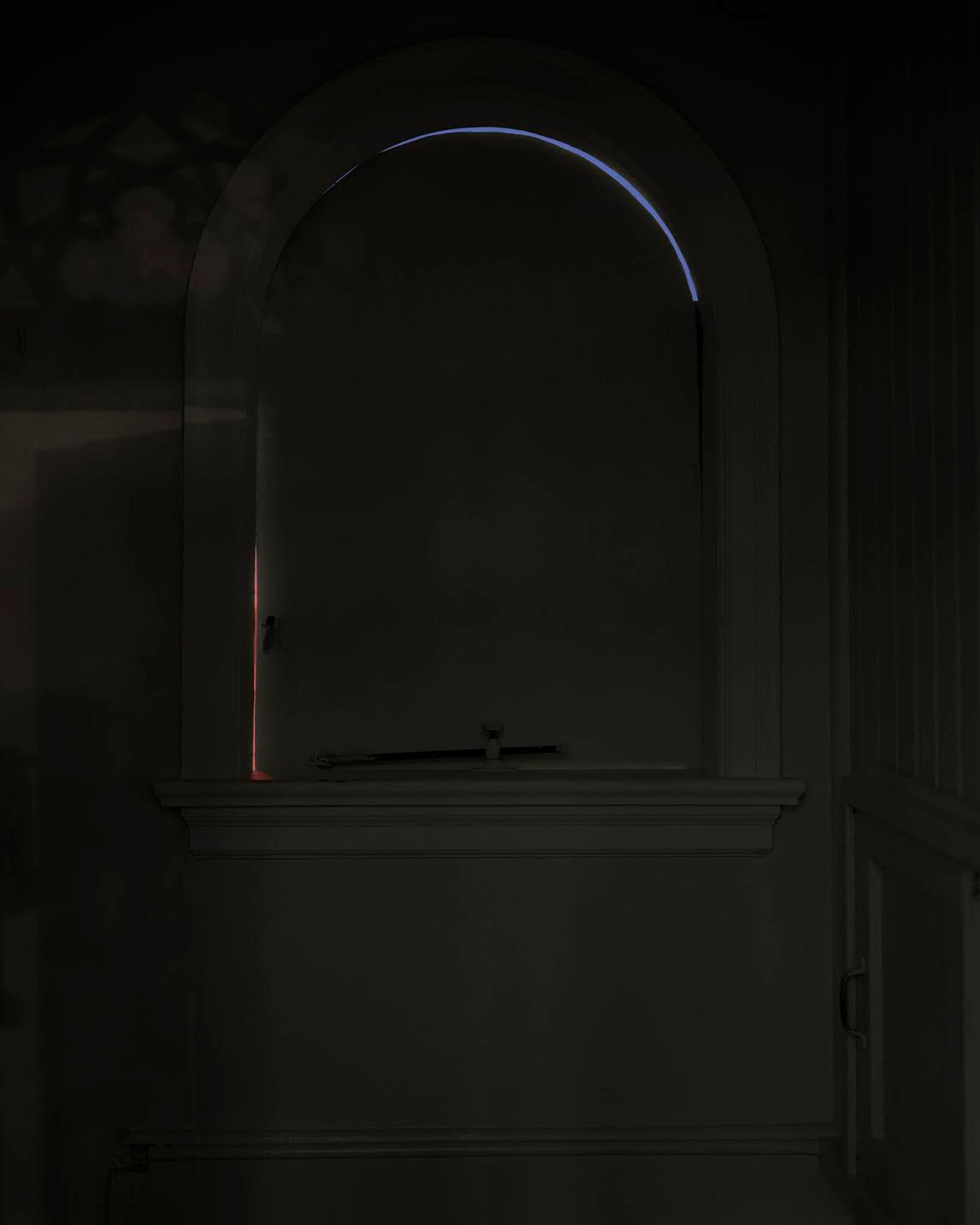

S. Billie Mandle: I begin with light — any light — but especially light within darkness, a sense of luminosity. With this picture I wanted to show the red and blue glow behind the window; the film captured other lights I never saw. I love light that appears out of nowhere. Billie’s new show “Reconciliation” is at Abakus Projects Jan. 5-28.

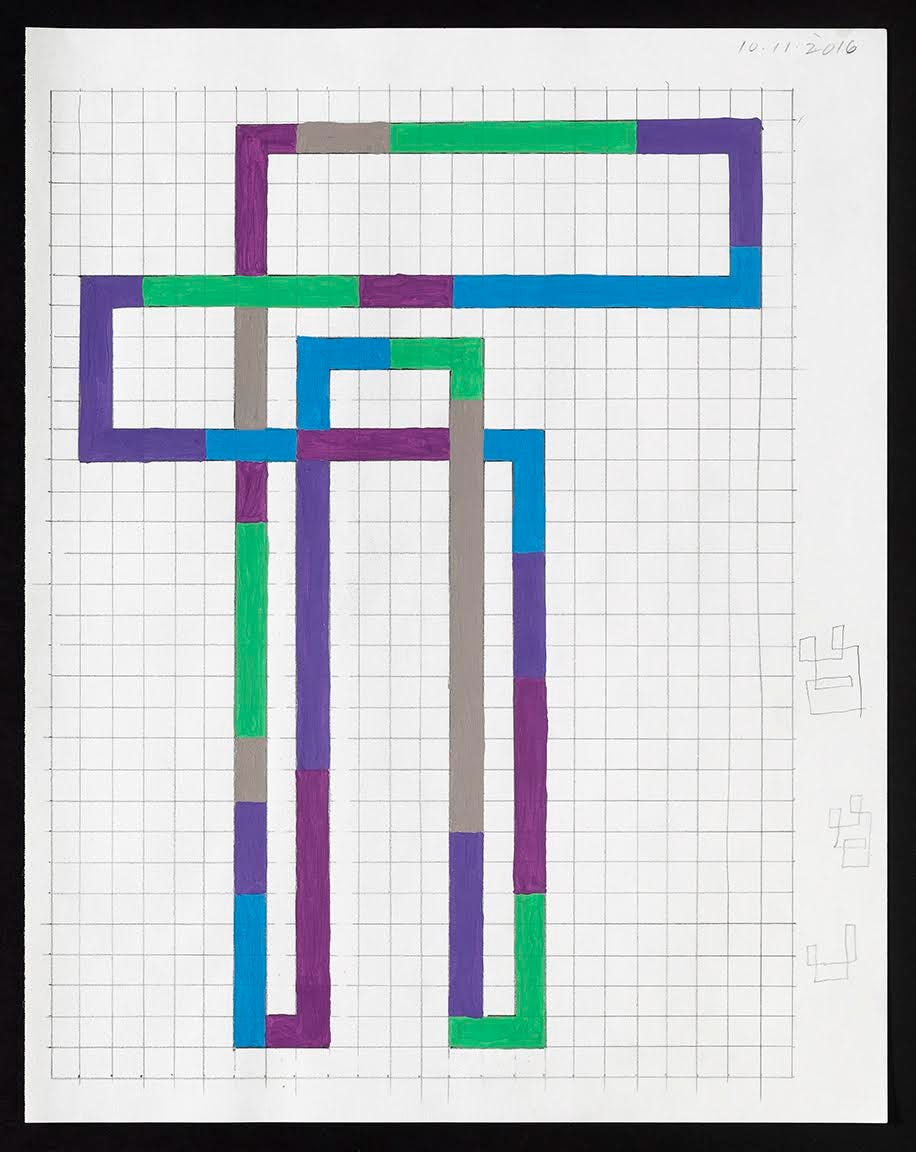

John Guthrie: I started formally keeping sketchbooks in 2006 as a way to organize and elevate my preparatory drawings to the level of my finished work. They have since become integral to my practice; an archive of evolving ideas and a generative playing field where forms take shape. I begin my sketchbook work by drawing grids to personal dimensions and then exploring compositions within those parameters. The method goes back to my early career as an aerospace engineer in the 1980s when my job was to hand-design parts for aircraft on one-hundred-square-per-inch gridded paper. This is how I first learned to draw years before enrolling in art school. It is also where I recognized the expansive possibilities of abstraction and problem solving within defined structures, concepts that drive my work to this day. John’s sketchbooks are on view in “Northeast Deconstructed” at Pulp Holyoke through Jan. 7.

Marlon Forrester: The process of starting a work of art is simple, I give myself permission to fail.

Any preconceived notion of rightness and wrongness becomes intertwined with my approach to artistic content that may have a cultural or formal meaning through the different juxtapositions of compositional elements.

I ask myself these questions: Do the tools I'm using lead me to navigating the entire whole or part of the whole through my desire for control? Where does my ego stand in relation to my need for improvisation?

If I observe my repetition of a movement and instinctually distort the order what will be the result as pleasure or disbelief.

What a great approach you've taken for this set of reviews! Asking the most basic and interesting question of all--how do you begin? It's the big question that everyone wants to know about the creative process. What I l love about the set of responses here are both the overlaps and the uniqueness. I love the conversational tone here.!

so resonant! -- exploring the layers of understanding and experience which all evolve over time, following the lead of the materials you use. The more I paint, the less I want to impose my will on the paint and the more I want it (and the paper/pen) to lead me down an interesting trail.

i recently was doing a deep clean of the house, and decided to dust off and reorganize 12 years of journals. i rather thought they'd be full of crap but there was a lot of good stuff in there and i was inordinately pleased to note my progress in -- as you said -- following my heart.

Keep following yours, Cate !